The various merits of the different shotgun actions are as hotly debated today as they were at the time of their invention. This guide takes you through each one. By Simon Reinhold

What exactly is a shotgun action? How do you tell one action from another? How were shotgun actions invented? All these questions and more will be answered in this guide so by the end you will be able to answer confidently to anyone questioning your shotgun action knowledge in the gun bus.

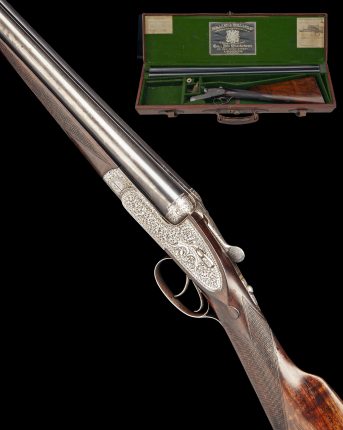

GUIDE TO SHOTGUN ACTIONS

Trigger-plate actions have all working parts mounted on the trigger plate. Many over-and-unders use a modified form of this design

The action is the beating heart of a shotgun. It is the canvas for the engraver’s artistry and has been the subject of snobbery, rivalry, genius invention and hard-nosed litigation throughout its development. All this energy and effort is for one simple purpose: repeatedly and reliably to translate a trigger- pull into a detonation.

It was the detonation of the charge that much of the progress in gun design in the latter half of the 19th century was connected. With the development of centrefire cartridges and Stanton’s patent rebounding lock of 1877, the breech-loading centrefire hammergun was perfected. But with all the floating or island locks, back-action sidelocks, bar-in-wood sidelocks and baraction sidelocks, the hammers remained external. Alongside this torrent of activity in the 1860s and 1870s, a side current of invention had begun to increase in flow and it was to split the kingdom into thirds. These were to become the three main action types used on the hammerless side-by-side shotguns: the sidelock, the boxlock and the trigger-plate round action.

The Purdey sidelock side-by-side is built on the action patented by Frederick Beesley in 1880

There are three ways you can cock a gun without applying one’s thumb to an external hammer: using a lever, using a spring or by using the weight of the barrels. George Daw improved another’s idea and patented a hammerless snap action in 1862 that was cocked by pushing forward an underlever. It was one of the first hammerless designs but it failed to inspire the shooting man as it was ungainly when compared with the beautiful lines of the hammerguns of the time. Daw’s model was followed by Murcott’s Mousetrap, Gibbs & Pitt’s hammerless action and Woodward’s Automatic. All important variations on a theme and all less beautiful than what had gone before. As with many human endeavours the majority are staunch traditionalists but a minority of early adopters like to take advantage of the latest developments. Of those named so far only Gibbs & Pitt, based in Bristol, were outside London. But away from the capital, further north other developments were taking place that would rival and surpass what was happening down south.

TRUE INFLUENCERS OF SHOTGUN ACTIONS

The term ‘influencers’ is much bandied about today, but true influencers in the gun trade were those individuals with equal amounts of vision, imagination and determination to bring their ideas to fruition. Two such men existed at Westley Richards & Co in Birmingham. John Deeley was the managing director of the firm and William Anson was the foreman of the machine shop. Between them they patented in 1875 the Anson & Deeley boxlock. Like many of the greatest inventions, it was relatively simple. It acquired its name from the fact that the internal parts are housed inside the metal box of the action. The weight of the barrels dropping down on opening the mechanism to reload acted on two cocking dogs protruding out of the knuckle. These then cammed up the mainspring and the tumbler, which in turn engaged the trigger. It was robust, far easier and quicker to make than its counterparts, and went on to be licensed to gunmakers around the world. It was also relatively cheap to manufacture, not necessarily a good thing in the eyes of many in the upper echelons of shooting society.

Like so many of the greatest inventions, the Anson & Deeley boxlock was relatively simple

As with most groundbreaking ideas in gunmaking, others took inspiration and a little way across Birmingham, WW Greener brought out his Facile Princeps in 1880. Westley Richards sued for patent infringement and eventually, in the highest court in the land – the House of Lords – it lost. More complex than an Anson & Deeley boxlock, though similar on the outside, the Facile Princeps was in fact substantially different.

Gunmakers in Scotland had been studying developments carefully. John Dickson’s early hammerless guns were built under licence on the Anson & Deeley patent. James MacNaughton, who had been apprenticed to John Dickson, had gone his separate way in Edinburgh and, after conversation with a German gunmaking acquaintance, came up with an elegant lever-cocking, skeleton-action shotgun with the working parts positioned on the trigger plate. It was lightweight, balanced and a joy to use. Using an elongated top-lever, its graceful lines didn’t startle the conservative landed gentry of Scotland.

A little way across Edinburgh the gunmakers at John Dickson, MacNaughton’s former master, were watching. Six months after MacNaughton’s patent John Dickson came out with a trigger-plate patent of his own. He too borrowed from another, Daniel Fraser, and went for a protruding tongue on the fore-end and iron that in its turn operated a slide inside the base of the action (Fraser’s was on the outside of the base of the action) that worked on the weight of the barrels dropping. Because all the working parts of the action are on the trigger plate, this allowed a lot of metal to be rounded off the bar of the action without losing any of the inherent strength. These developments and the later inclusion of ejectors, resulted in one of the iconic designs in gunmaking. The weight distribution of a Dickson round-action trigger plate is further back between the hands and lower in the action. Like a race-tuned sports car chassis they are fast-handling and responsive, built primarily for the swiftest of gamebirds: Scottish red grouse. The trigger-plate action has been adopted widely and modified by many of the modern manufacturers of over-and-under guns because of these superb handling characteristics.

It is far easier for your fellow guns to see the apparent cost of a sidelock than it is to see that of a boxlock or a round action, not least as the sidelock has a larger canvas on which the engraver can practise his art. That is not to say that best boxlocks were cheap to buy in comparison. Many of the trade catalogues of the late Victorian gunmakers have best boxlocks equal to and in some cases exceeding the price of best sidelocks, but from a buyers’ perspective they wanted others to know they had spent good money on the gun in their hand. Why would a gentleman concerned with his image buy a boxlock when he could buy a sidelock for the same money? Some makers tried to address the shortage of engraved metal by fitting sideplates to their boxlocks – a feature often seen today on many of the most popular over-and-unders. The fact remains that a best boxlock is a superb gun and in many cases these days far less prone to malfunction than a London best sidelock after years of ‘servicing’ from garage gunsmiths. They represent some of the best value in the gun-buying market. Round actions have always commanded a premium, being relatively rare and having a devoted following.

The Holland & Holland Royal evolved from the design patented by John Robertson and Henry Holland in 1883.

While London gunmakers may have disregarded the trigger-plate round action and thought of the boxlock as an inferior, northern pretender, this was a little disingenuous. Before the perfection of the sidelock, Holland & Holland had taken full advantage of the Birmingham makers Scott & Baker’s patent hammerless gun. With its dipped-edge lockplate, giving plenty of scope for the engraver to show his skill, it was for them reminiscent of the best sidelock hammerguns. The company marketed and sold so many of what it termed its ‘Climax Safety Hammerless’ guns that many thought the patent was its own. It was a variation on a barrel cocker as two cocking rods within the action were pulled forward by hooks on the flats as the barrels dropped down.

All the London makers sold Anson & Deeley boxlocks on to their clients, who were often looking for a cheaper gun for a nephew or other relative at the same time as buying their pair. Almost all of these guns were bought in from the Birmingham trade and finished in London. At Boss & Co, ‘builders of best guns only’, John Robertson, who acquired the company in 1891, outsourced Birmingham trade boxlocks of the highest quality and finish under his name, keen to fulfil clients’ needs while not compromising the company’s reputation.

As the classic sidelock action was part of the gunmaking legacy of many London names, they devoted as much time and energy to perfecting it as had been devoted to the development of the boxlock. The early running was made by two men both called John Rogers working together. Their 1881 patent for a sidelock employed a similar barrel-cocking design with attendant cocking dogs and was widely adopted under licence by the trade makers that had no patent of their own. Then in 1883 John Robertson, later of Boss & Co but at this time outworker to the trade under his own name, teamed up with Henry Holland to patent and then refine a barrel-cocking gun that cocked one lock on opening and the other on closing. This brilliant design would later evolve into the Holland & Holland Royal hammerless sidelock ejector, which has become one of the most classic and desirable guns of all time.

The components that make up a Holland & Holland Royal sidelock action

Frederick Beesley, a prolific patentee and former stocker for James Purdey & Sons, went down a different path, and in 1880 used both limbs of the mainspring to at once spring open the action to speed up loading and to re-cock the tumblers. It was this patent he sold to Purdey, receiving £85. The two cams protruding through the action are most familiar on Purdey self-opening sidelock ejectors. He refined and simplified his ideas in subsequent patents.

ONGOING DEBATE

The letters pages of various publications have played host over the years to many debates over whether a sidelock is inherently a better gun than a boxlock or whether a trigger-plate round action is better than both. It has been argued that, with their more refined parts, a sidelock and a round action have better trigger-pulls than a boxlock. But it is likely that such differences are lost in the modern era of increasingly large shot weights and sizes. Sidelocks are more complicated and costly to build than the simpler action of a boxlock and the skills to do so properly are sadly diminishing. Boxlocks are regarded by some as stronger through the head of the stock than sidelocks and that argument is countered by those who say that the action bar of the sidelock has greater robustness. There is no denying the inherent metallic strength of the round action and the handling is like no other gun I have shot. It either suits you or not; few find themselves on the fence.

This trio of shotgun actions, at the heart of the side-by-side shotgun, have merits that are as fiercely debated today as they were at the time of their invention. Long may the debate continue.